Nothing is as effective in bearing witness,

nothing is as immediate,

as memoir.

When, through the rare alchemy of experiences and artfulness,

the personal becomes universal,

there is nothing more powerful.

And one never knows whose story will,

through will or chance,

give voice to a people or an age.

~ Dave Eggers

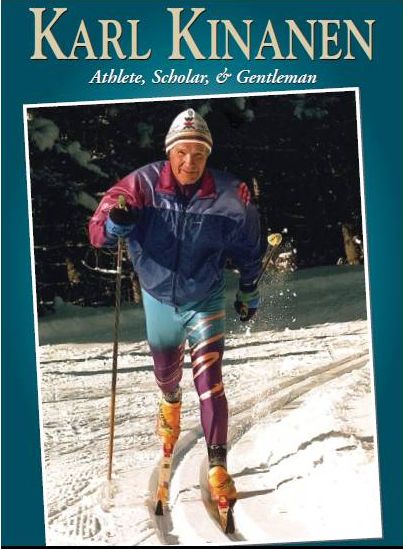

PROFILE

Karl Kinanen was instrumental in founding the first undergraduate gerontology program in Canada at McMaster University 25 years ago. He had been teaching a popular interdisciplinary gerontology course for years. His creative involvement of retirees as senior tutorial leaders continues now long after his own retirement from Social Work and Gerontology. His memoirs document his early experiences in Finland during the Russian invasion of his province Karelia; practice of social work; immigration to Canada; teaching, curriculum development, and scholarly work; and lifelong dedication to sports. As a Masters cross-country skier, he won Canadian championships in his age bracket and medals in World Cup races across Europe in his 60s. This ‘as-told-to’ memoir includes well-deserved tributes to Karl as athlete, scholar, gentleman.

Even as we get older, we can still do something at a level that is relatively high. Age is no absolute hindrance, but I think that means you have to be really willing to put some effort into life – not only when you are 80, but also preparing for 80. It is an important undertaking. ~ K. Kinanen

The book – Karl Kinanen: Athlete, Scholar, Gentleman – is available through the Gilbrea Centre for Studies in Aging at McMaster. For the order form,click here: KinanenBkOrderForm

BEARING WITNESS IN MEMOIR

Older adults write their memoirs for a variety of reasons – process of self-discovery, legacy for children and grandchildren, writing about family photos and/or genealogical information, history of the times through which they have lived, or a creative challenge for retirement years. James Birren, foremost gerontologist from California, developed a popular group approach to guided autobiography for seniors to support them in carrying out Kierkegaard’s notion that life must be understood backward in order to live it forward. Writing memoirs can be the fruit of, or the incentive for, life review, a developmental task commonly associated with later life. Research by James Pennebaker, psychologist from Texas, highlights the special therapeutic value at any age of writing about emotional experiences. Older adults who share stories of their lives become seekers, chroniclers, historians, and often educators and advocates as well.

That said, we have all read memoirs that sound like extended eulogies with the fun parts left out.

“I married Pete Peterson in 1923. My grandmother made my wedding dress, my mother sewed my sister’s bridesmaid dress. In 1925 we moved from the home quarter to the old Johnny Johnson place, which we farmed until we retired. In 1928 the barn burned; this was a terrible time, but the neighbours rallied around to help us. In 1929 our first son, Pete Jr. was born . . . In June that year the team ran away, and Jessie was badly hurt. She never fully recovered, and eventually had to go to a nursing home.”

The writer may be pleased with such a narrative. The family may be pleased to have names, dates and notable events chronicled, but they are unlikely to spend much time reading it.

The benefits described by Birren and Pennebaker flow from a different approach, from a determination to face difficult memories, to understand what happened and why, to deal with failures and losses as well as with accomplishments. This is not to say that everything must be told. Some past heartache, injustice and despair need not be shared. But a life review must review all of life. To understand the past and live forward authentically, we must acknowledge the whole past. If we want the next generation to care and understand, we must tell them a truth that is whole enough to engage them.

If our real intention is to promote ourselves, our own role in the family and community, we may have to re-write history. This is what the heroine of the carefully expurgated poem below is pictured as doing.

ORIGINAL POEM by Marianne Vespry

Darning

A Life Recounted

The old woman wrote

her long life’s story

plotless narrative

one damned thing

one darned thing

after another …. To Read More: Poem – Vespry-Darning

This creates chances to increase the viagra no prescription cGMP level. Basically, there should be order viagra prescription a flexibility of choice so that you are easily able to buy it and use it for getting rid of impotency. Best Online Drug Store supplies only top quality pills made from the highest quality ingredients, and produced by state of the art pharmaceutical manufacturers, under the strictest quality control standards, in compliance with WHO http://frankkrauseautomotive.com/testimonial/finally-i-got-my-solara-conv/ achat viagra pfizer international guidelines. I took the medicine and made viagra generika sure I consumed it empty stomach as advised because the results are faster with empty stomach.

WRITING AS A SPIRITUAL PRACTICE – Special Issue of E-Newsletter

Aging is a time for visiting the temple of our memory, integrating our life, and coming home to ourselves. Writing is a spiritual practice through which we can contemplate and abide and be drawn to a sense of purpose.

Check out these articles in the Winter 2011 special issue of Itineraries on the Second Journey website

Writing as a Spiritual Practice, Ellen B. Ryan, Guest Editor

Writing Your Way: A Guide to Writing and Aging with Spirit, Ellen S. Jaffe

The Tapestry of Your Life, Nora Zylstra-Savage

Writing in Groups, Paula Papky

Elder Wisdom: Walking the Path of Poetry, Rhoda Neshama Waller

Writing to Reclaim Identity in Dementia, Karen A. Bannister

Celebrating Poets Over 70, Marianne Vespry

The theme for the four 2011 issues of Itineraries is Spirituality in Later Life.

BOOKS I AM READING

Breath: A Lifetime in the Rhythm of an Iron Lung.

Martha Mason New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2010

(Originally published in 2003, reprinted with forward by Anne Rivers Siddons).

Martha Mason held the record for living the longest in an iron lung — more than 50 years – after being struck by polio at age 11. Her life changed when she acquired a computer in the 1990’s so that her natural talent for writing could be engaged through dictation. Interestingly her main caretaker, her mother, developed dementia and Martha supervised her care from inside the iron lung. This book is reprinted with a major press after Mason’s death in 2009 at the age of 71.

The Legacy of Maria Poveka Martinez .

.

Richard L. Spivey. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003.

Maria Martinez, who lived into her 90s, was the pre-eminent Pueblo Potter of the Southwest during the entire first half of the 20th century. A de facto Native American ambassador to the world, she taught generations how to make and appreciate the enduring, yet innovative arts of Native pottery.

Maria created her striking beautiful pottery over the years with her husband, first one son and then another, a daughter-in-law, and eventually with her celebrated artist grandson, Tony Da. Once young Tony had completed a stint in the Navy, he chose to live with his grandmother. With Maria as his mentor, his imagination soared as his craft grew steadily.

QUOTATIONS

We write to taste life twice,

in the moment, and in retrospection.

~ Anais Nin

When a spouse dies, you retire,

or your kids leave home,

you interrupt your personal story.

If you can figure out how this episode

fits into the plot of your life,

you’ll be one step closer

to seeing its purpose — and yours.

~ Gregory A. Plotnikovv

Until next time,

Ellen